Demystifying Continuous Integration, Delivery, and Deployment

28/Dec 2015

This Calm.io blog recap was originally written and posted by me on December 28, 2015 at http://calm.io/2015/12/28/demystifying-continuous-integration-delivery-and-deployment/, and slightly enhanced on February 18, 2018, be sure to see the Postscript for more perspective!

Traditional software engineering organizations separate duties between teams for development, build, testing/quality assurance, release, and operations. This approach increases work by hiring people in silos, fostering separation of duties, manual hand offs, and injects human issues into the process of delivering quality software. How does DevOps help solve traditional problems of scaling human efforts to speed the delivery of increasingly complex software to the customer?

I defined the term DevOps in the opening blog entry: I Dream of DevOps, but What is DevOps? DevOps spans the entire spectrum of software engineering and the software development life cycle, seeking to reduce the friction in delivering value to customers. It is the DevOps mission to solve the very problem posed to traditional engineering organizations by automating the build and release of software, thereby achieving Continuous Integration, Continuous Delivery, and ultimately Continuous Deployment.

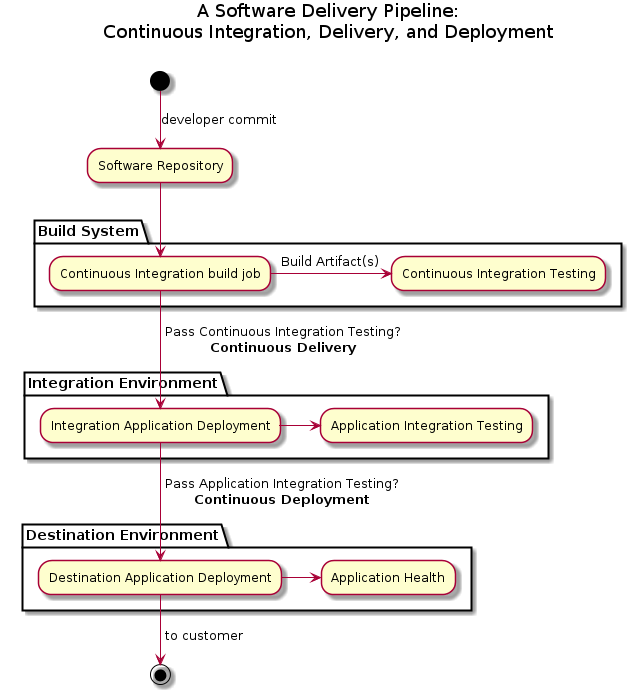

Software Delivery Pipeline

The journey from a developer to the customer can be represented by a flowchart that ties together people and systems to build and release software. Different software teams at the same organization can have unique processes, tools, and timelines to produce their software, so multiple software pipelines are driven through automated build and release facilities.

Here is an overview of an automated software delivery pipeline:

The goal is to build and test software artifacts, then deliver and test them in a whole application context, and finally deploy them in an automated fashion. I will define and explain these terms in depth, but let me walk you through the stages of the software delivery pipeline from a high level:

- A developer commits changes to the Software Repository

- Continuous Integration (CI) = a Build System periodically runs a Continuous Integration Build Job which builds and performs Continuous Integration Testing on the build artifact(s) in isolation

- Continuous Delivery = passing Continuous Integration Testing promotes the artifact(s) to an Integration Environment for Application Integration Testing as a whole application

- Continuous Deployment = passing Application Integration Testing promotes and deploys the artifact(s) to a Destination Environment.

Build Systems

It is extremely rare to find a software engineering organization taking the pains to unify their development environments with the aim of making them consistent and immutable for all developers. It is a typical practice for developers to customize their environments to make themselves as productive as possible. While there is some justification to this policy, there is also a repeated productivity cost when the excuse “it worked on my laptop” is used. This is a signal for DevOps evangelism and it will be the topic of a future blog entry!

Given that developer environments vary, their local development build results can also vary and challenge reproduction elsewhere due to any uniqueness. The traditional answer for software engineering is to adopt a build system which should be:

- documented and reproducible: so it can be a reference to understand deltas from local development

- maintained and consistent: up to date facilities are also placed under change control so that the environment does not drift from a known good configuration

- official and centralized: allowing the organization to converge and manage their methodology and policies

As the next stage in the software delivery pipeline after the software repository, build systems can expand to incorporate additional organizational processes. However, build systems are often ignorant of the entire software development life cycle and require significant investment to customize, thereby concentrating risk, complexity, and dependencies for an engineering organization. As suggested above, centralized build systems can represent contention between official and local developer builds. Optimizing build systems and refactoring the software development life cycle pipeline should be a DevOps exercise in order to address all organizational needs, suggesting yet another future blog entry, but let us return to the topic of continuous integration.

Continuous Integration

A build system allows an organization to automate Continuous Integration (CI), which is the practice of periodically creating the latest version of the software based upon the current state of commits to the software repository. CI is meant to catch the source of build errors as early as possible because developers should always create buildable software. Engineering organizations vary their CI approach because they have different values and needs. The major factors to CI are:

- Period:

- static = CI period will be every weekday, overnight, or several times a day

- ad hoc = CI build with every developer commit

- Repository Scope:

- certain branch(es) of the software repository will be built (e.g. the head of the mainline branch versus other branches, such as a release branch)

- a (sub)set of the software repositories will be built

- a (sub)set of each platform will be built

Organizations vary the period and repository scope variables for a number of reasons, primarily to control the speed to deliver feedback results because a CI build across the full set of permutations of software repositories, branches, and platforms could take many hours to generate results. The process to fix a broken CI build becomes the next point of differentiation.

Broken Builds

The governance of a broken CI build leads to the next set of variables:

- Notification:

- Does a broken build result in an automated communication to the developer and/or the team?

- What medium is the automated communication use: email, instant message/chat, dashboard/information radiators?

- Remediation:

- What are the policies for remediation of a broken CI build? Is it the highest priority to fix, outranking feature development and other emergencies?

- Who is responsible to fix? The developer and/or the team?

- How does one communicate the remediation in process?

- Reversion:

- Is there an expiration period for remediation before the source commit is reverted, putting the CI process back into a known good state?

- If the expiration period is too long, have other commits been ignored that would result in a CI build failure?

Even after controlling the period and repository scope of CI, there are many questions for how to fix a broken CI build. During the remediation period, the organization is exposed to increased risk of a new source of broken builds with every ensuing developer commit. This causes many organizations to evolve by changing the period variable from a static value to an event based definition.

Next Generation Continuous Integration

With the advent of cloud computing providing on demand compute scale, organizations can decrease the period while increasing the repository scope to achieve Continuous Integration with increased coverage and speed to results. This raises the confidence in the state of the software repository to produce buildable software. Organizations change the CI variables to:

- Period:

- ad hoc = CI build with every developer commit

- Repository Scope:

- increased coverage of branches, repositories, and platforms for parallel CI builds

- Reversion:

- a broken CI build results in the developer commit being reverted

By automatically reverting a commit for a failed CI build, the risk and remediation period are minimized to the CI process time. An optimization exercise is usually taken to control the scope of ad hoc CI for quick results while an exhaustive CI build can be scheduled with a static period (such as overnight) to achieve the best of both worlds.

Many organizations take the next step to incorporate CI as a pre-commit check, blocking the candidate commit entirely if a CI build fails. By uniting the software repository and build system to work together, the goal to prevent a broken build is achieved. Next generation continuous integration omits the remediation and reversion variables of the static periodic CI process and eliminates broken builds because it is truly continuous!

However, pre-commit CI build checks still fall short of achieving DevOps agility when considering the entire software development life cycle. A passing build does not guarantee software quality or the ability to be delivered until those dimensions are exercised, leading to the next section, “Continuous Integration Testing” which extends the software delivery pipeline to enable next generation CI, continuous delivery, and deployment.

The traditional software engineering organization uses the successful build results (called build artifacts) on their build system as an artifact repository where they are handed off to testing and operations teams to consume. There exists an entire industry category for software distribution of build artifacts and management, but we will defer that discussion for another blog entry.

The testing and quality assurance teams consume the build artifacts to assess the quality of the features across the permutations of platforms for delivery. However, the existence of manual hand offs to testing and later to operation teams signals the need for DevOps evangelism when we hear “my work built fine, so there is no problem as far as I am concerned!” Before the days of DevOps, traditional testing happens before any operations and deployment considerations were addressed.

Increasingly, developers are writing unit tests for their code while manual quality assurance and test work is being automated and delegated to test systems and test providers. I define Continuous Integration Testing as the sum of all the automated tests from various teams, systems, and providers that are invoked during CI.

Continuous Integration Testing

Now that CI can eliminate broken builds, the next step is to test the build artifact(s) for new functionality and existing functionality regressions, thereby guaranteeing a minimum software quality threshold. This is called Continuous Integration Testing and it invokes automated tests on the new build artifacts. While this stage may represent the state of the art for many organizations, huge amounts of variability exist in automated continuous integration testing because it can represent an exponential increase in test scope and time to deliver results. Major areas of test scope include:

- Test Systems/Providers:

- Does the official build system run tests inside the build environment or do complex testing requirements force delegation to external test system(s) and/or provider(s)?

- How are test systems/providers held to the same standards as the build system to be documented and reproducible, maintained and consistent?

- How does one develop and test the test systems themselves when they also represent complex software?

- Unit Testing:

- How many new features are tested?

- How many existing features are tested for regression?

- How long does it take to test the full set of features, i.e. how to optimize functional unit testing in context of CI and outside of CI?

- Have our mock objects diverged and need update to model the rest of the application components, external systems/providers, and APIs, i.e.: how to test our mock objects?

Just as before, there is a trade off between time to test and exhaustive test scope. Assuming an optimization of the unit test scope and that the test systems/providers have cloud scalability, CI can achieve continuous integration testing results with speed. For the best of both worlds, adding periodic exhaustive continuous integration testing allows further confidence software quality and brings down the barriers to automation of delivery.

Monolithic Application Refactoring

It is natural to align all of the engineering teams into delivering a single, composite piece of software: a monolithic application. However, the challenges of scale and coordination ultimately fragment the monolith over time to evolve to a distributed application architecture. You can understand the turmoil engineering organizations have when they decide to refactor their monolith into components because they simultaneously decrease the complexity of testing each component while increasing the complexity of testing the whole integrated application because all of the components must be assembled.

Refactoring the monolith benefits each team to advance their features, tests, and deployments independently, achieving engineering agility. This approach is exemplified by Microservices, a logical candidate for Immutable Infrastructure, and a future blog entry topic!

Unless CI is building a monolith, each build artifact now represents an isolated component of a larger application system that must work together. This increases the scale and complexity of testing and deployment; it must be addressed via DevOps automation to test the entire application build artifacts together.

Application Integration Testing and Continuous Delivery

Given the challenges of microservices, distributed application components, and dependent systems, testing must expand to cover the full application. While continuous integration testing merely tests a build artifact in isolation, a new set of tests must exercise the application as a whole and I call it application integration testing.

In the context of the software delivery pipeline, the term “integration” is overloaded and it must be distinguished: it is important to say that continuous integration (CI) does not necessarily imply any testing at all. However, application integration testing can be added to continuous integration testing and it is required for continuous delivery.

Continuous delivery is the instantiation of the application to an integration stack/environment/deployment for application integration testing. This test deployment also represents the most obvious goal or cross over point into DevOps for many organizations. The complete application must be deployed and orchestrated with the newest build artifact along with previously validated artifacts for application integration testing to proceed. This requires a number of new capabilities captured as variables:

- Artifact Management:

- What is the set of artifacts necessary to compose the entire application?

- What are the existing, validated versions of each artifact for reuse with the candidate build artifact(s)?

- Deployability:

- How to bring up a set of new resources, each with the proper build or existing artifacts, and configured to work together?

- Can it be accomplished with configuration management or other methods? How about handling dynamic configuration management?

- Application Orchestration:

- How do insure that the order of each resource/artifact dependencies are satisfied to bring up the application as a whole? i.e.: the back end services must be ready before the business tier logic can start to connect to them and so on throughout the application before testing can start!

- Application Integration Testing:

- Functional unit tests exercise a feature on a build artifact in isolation, can you retest the application features on the whole system?

- Does your integration testing include performance, scale, and security testing?

When an organization provides answers to the above, it can create an ephemeral test environments for application integration testing on deployed build artifacts. The application integration tests can be optimized into tests which exercise a small set of critical features and transactions throughout the entire application life cycle in order to consume as little time as possible for the next generation, ad hoc CI process.

This is how a DevOps approach can enable next generation continuous integration: not only are broken builds eliminated, but we can achieve a minimal set of software quality and deployability through automated application integration testing. Application orchestration and deployability are true examples of the blending of [DEV]elopment and [OP]eration[S] together.

Testing is a diverse area and the scope of performance, security, longevity testing can only follow and build on application integration testing: they are often omitted or performed manually and represent other areas ripe for automation.

Continuous delivery is the deployment of a fully orchestrated application instance for application integration testing and we will reuse this methodology for continuous deployment.

Continuous Delivery and Continuous Deployment

What is the difference between Continuous Delivery and Continuous Deployment? Ideally, very little except for test scope and destination.

Application integration testing is an example of continuous delivery to a test application environment. Each test environment should be treated as short-lived, ephemeral instances (cattle) so that each test is isolated and fully reproducible, prevent corruption because no state can be passed between (pet) test environments. Once a build passes the optimized application integration test, the process could repeat that application deployment to a longer lived instance for manual and long term test runs (for full integration, performance, longevity, etc. testing) and this would be continuous delivery to a test application environment for the QA/test teams.

Longer lived test environment instances represent an infrastructure management challenge that an organization will decide based on the need to perform forensics, preserve reproducible bugs, and hand off to teams to perform manual tests. All of these represent automation friction which can prevent or block ephemeral continuous delivery and another call for DevOps evangelism!

If exhaustive application integration testing passes, then continuous delivery could target staging and even production applications automatically, achieving continuous deployment, i.e.: continuous deployment is simply continuous delivery to production. Each engineering organization must determine the scope and period of automated, exhaustive application integration testing, which returns to the periodic integration model, but remains a frictionless path to achieve our DevOps definition of delivering value from the developer to the customer.

Postscript 2018-04-13: Netscape Tinderbox

When I started work for Netscape in 1996, it was the first time I had worked for a software company. I had not realized that a continuous integration build server was something fairly new: Tinderbox merely existed and it made perfect sense for release engineering to identify broken builds. A recent article pointed me to a reference which reveals this was not the case, it was pioneering work!